by Mish

Selgin made similar comments about Chris Whalen, Chairman of Whalen Global Advisors LLC, in two supporting links.

I also received a Tweet from economist Professor Steve Keen who said: “Mish Nails It“.

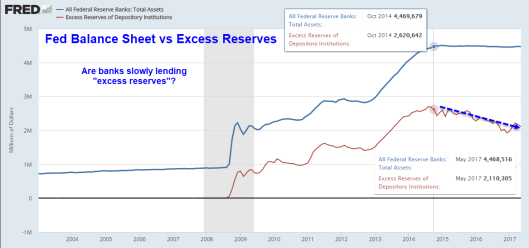

Both viewpoints cannot be right. Let’s explore competing viewpoints on lending excess reserves, banks hoarding cash, and free money banks receive from the Fed for interest on excess reserves.

Mish Statements

“Excess reserves are a function of the Fed’s balance sheet and those reserves do not change whether a bank lends more or not.

There is no “demand” for excess reserves. Rather, the Fed has crammed excess reserves into the system and has decided to pay interest on them.

- Mathematically speaking, excess reserves cannot spur lending.

- Banks are not paid $22 billion to “not lend” $2.2 trillion as many contend.

- Banks are paid $22 billion because the Fed decided to do so.

Whether or not banks lend has nothing to do with interest on excess loans. Rather, the decision to pay interest on excess reserves is simply $22 billion in free money to banks every year, at taxpayer expense.”

Steve Keen

Mish @MishGEA nails the nonsense about banks wanting “excess reserves” still spouted by @federalreserve economists https://t.co/Iln2jmZ3lX

— Dr. Steve Keen (@ProfSteveKeen) April 18, 2017

Selgin: Interest on Reserves

In Interest On Reserves, Part II, Selgin writes.

“Of the many bemusing chapters of the whole interest-on-reserves tragicomedy, none is more jaw-droppingly so than that in which the strategies’ apologists endeavored to show that paying interest on reserves did not, after all, discourage banks from lending, or contribute to the vast accumulation of excess reserves.

But let us set our befuddlement aside, in order to allow our authors to dispute the view that the vast post-IOR accumulation of excess reserves was evidence that the Fed’s emergency loans and asset purchases weren’t serving to “maintain” an adequate flow of credit:

To the contrary, the level of reserves in the banking system is almost entirely unaffected by bank lending. By virtue of simple accounting, transactions by one bank that reduce the amount of reserves it holds will necessarily be met with an equal increase in reserves held at other banks, and vice versa. As described in detail in a 2009 paper by New York Fed economists Todd Keister and James McAndrews, nearly all of the total quantity of reserves in the banking system is determined solely by the amount provided by Federal Reserve. Thus, the level of total reserves in the banking system is not an appropriate metric for the success of the Fed’s lending programs.

A gold star to all who spot the fallacy here. For those who can’t, it’s simple: “reserves” and “excess reserves” aren’t the same thing. Banks can’t collectively get rid of “reserves” by lending them — the reserves just get shifted around, exactly as Walter and Courtois suggest. But banks most certainly can get rid of excess reserves by lending them, because as banks acquire new assets, they also create new liabilities, including deposits. As the nominal quantity of deposits increases, so do banks’ required reserves. As required reserves increase, excess reserves decline correspondingly. It follows that an extraordinarily large quantity of excess reserves is proof, not only of a large supply of reserves, but of a heightened real demand for such, and of an equivalently reduced flow of credit”

IOER and Banks’ Demand for Reserves, Yet Again

Here are some Selgin snips from IOER and Banks’ Demand for Reserves, Yet Again.

“In our recentAmerican Bankeropinion piece, Heritage’s Norbert Michel and I argue that, if the Fed is really serious about shrinking its balance sheet, it had better quit paying interest on banks’ excess reserves (IOER) as well. How come? Because the current, relatively high IOER rate is contributing to a strong overall demand for excess reserves, while a shrunken Fed balance sheet will mean a reduced supply of reserves. Reducing the supply of reserves while doing nothing to reduce banks’ demand for them is a recipe for demand-driven deflation, which is a monetary policy no-no.

Predictably (because it has happened every time I write on this topic) our article generated several comments to the effect that we didn’t know what we were talking about, because banks couldn’t possibly prefer the meager 100 basis points they can earn by holding reserves (or something less than that, if they are obliged to pay FDIC premiums) to the far greater amount they can earn by making loans.

The remarkable thing about these criticisms is that they all appear to deny that banks (or some banks, in any event) are in fact sitting on large amounts of excess reserves, and that they are, to that extent, settling for a return on those reserves of 100 basis points or less, instead of swapping reserves for other assets”

Excess Reserves

Let’s take a step back and look at the definition of “Excess reserves“.

“In banking, excess reserves are bank reserves in excess of a reserve requirementset by a central bank.”

Required Reserves

“The reserve requirement (or cash reserve ratio) is a central bank regulation employed by most, but not all, of the world’s central banks, that sets the minimum amount of reserves that must be held by a commercial bank. The minimum reserve is generally determined by the central bank to be no less than a specified percentage of the amount of deposit liabilities the commercial bank owes to its customers.

[in the US] Effective 27 December 1990, a liquidity ratio of zero has applied to CDs and time deposits [e.g. saving accounts], owned by entities other than households, and the Eurocurrency liabilities of depository institutions. Deposits owned by foreign corporations or governments are currently not subject to reserve requirements.

Canada, the UK, New Zealand, Australia, Sweden and Hong Kong have no reserve requirements.

This does not mean that banks can – even in theory – create money without limit. On the contrary, banks are constrained by capital requirements, which are arguably more important than reserve requirements even in countries that have reserve requirements.”

One might superficially conclude that banks are lending reserves by looking at the above chart, but here is what’s really happening:

In the process of lending, a portion of the loan gets redeposited in instruments that have reserve requirements.

Thus, my statement “reserves do not change whether a bank lends more or not,” is incorrect even though it takes a long time to matter in a meaningful way.

Everything else I stated is correct because reserves, excess or otherwise, do not enter into bank lending decisions.

BIS Statement

Please consider BIS Working Papers #292 Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal, page 19.

“In fact, the level of reserves hardly figures in banks’ lending decisions. The amount of credit outstanding is determined by banks’ willingness to supply loans, based on perceived risk-return trade-offs, and by the demand for those loans. The aggregate availability of bank reserves does not constrain the expansion directly.

By the same token, an expansion of reserves in excess of any requirement does not give banks more resources to expand lending. It only changes the composition of liquid assets of the banking system. Given the very high substitutability between bank reserves and other government assets held for liquidity purposes, the impact can be marginal at best. This is true in both normal and also in stress conditions. Importantly, excess reserves do not represent idle resources nor should they be viewed as somehow undesired by banks (again, recall that our notion of excess refers to holdings above minimum requirements). When the opportunity cost of excess reserves is zero, either because they are remunerated at the policy rate or the latter reaches the zero lower bound, they simply represent a form of liquid asset for banks.

A striking recent illustration of the tenuous link between excess reserves and bank lending is the experience during the Bank of Japan’s “quantitative easing” policy in 2001-2006. Despite significant expansions in excess reserve balances, and the associated increase in base money, during the zero-interest rate policy, lending in the Japanese banking system did not increase robustly.”

Bank Credit vs. Reserves

Between July 2008 and May 2017, bank credit rose by $3.59 trillion. Required reserves rose by all of $134 billion.

Does Rising Interest on Reserves Hurt Lending?

Selgin says the Fed needs to halt paying interest on excess reserves to spur lending. Curiously, bank credit rose over $900 billion as the Fed was hiking.

If there is any slowdown in lending, it is due to the slowing economy or lack of good customers, not that the Fed is paying increasing amounts of money for excess reserves.

Loans and Leases vs Reserves

Selgin used loans and leases in his links, so I provide the above chart as an alternative to bank credit. One can look at M2 to see similar things.

Banks Lend, That’s What They Do!

Bakers bake, painters paint, homebuilders build, and bankers lend. That’s what they do.

If banks are not capital impaired, and they believe they have a good credit risk who wants to borrow, they lend. In the process, required reserves rise by a tiny amount.

But it’s capital impairment and creditworthy customers that drive the lending process, not reserves. The BIS has this correct.

Definition of Demand

Demand has a couple of meanings. In widespread use, demand is an imposition on someone (e.g. pay me or else).

What Selgin refers to as demand is the “desire of banks to hold money”. He cites $2 trillion in excess reserves as “proof” of “demand”. The statement is silly.

Banks did not demand $2 trillion in the classic sense, nor are they hoarding money because the Fed pays interest on reserve. Rather, the Fed crammed over $2 trillion into the system.

If banks had creditworthy customers willing to borrow, banks would lend. It’s what they do, and it is precisely what the charts I presented show.

Slow Elimination of Excess Reserves

Conclusions

- Banks lend if they are not capital impaired and they have customers deemed creditworthy. Reserves do not factor into banks’ willingness to lend.

- Banks are not demanding excess reserves. The Fed forced excess reserves into the system.

- Elimination of interest on excess reserves will not spur lending.

Selgin has things backward. There is not a demand for cash by banks that is holding up lending. Such a condition would occur if banks were capital impaired. Rather, there is a lack of demand for loans, by creditworthy borrowers, at a sufficient pace to quickly eliminate excess reserves.

As an aside, I am in favor of eliminating interest payments. Giving banks free money at taxpayer expense is galling.

Corrections

I added the chart on the slow elimination of excess reserves and corrected a few minor typos.

Mike “Mish” Shedlock